Preventing Suicide among

Men in the Middle Years:

Recommendations for

Suicide Prevention Programs

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 3

INTRODUCTION 5

SECTION 1 7

Understanding Suicide among Men in the Middle Years: Key Points

SECTION 2 12

Recommendations for Suicide Prevention Programs

SECTION 3 21

A Review of the Research on Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

ñ Scope and Patterns

ñ Risk Factors

ñ Protective Factors

ñ Suggestions from the Research Literature

ñ Conclusion

ñ References

SECTION 4 54

Programs and Resources

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

3

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years: Recommendations for Suicide Prevention

Programs was developed by the Suicide Prevention Resource Center (SPRC) at Education Develop-

ment Center, Inc. (EDC).

The following people contributed their time and expertise to the development of this resource:

Men in the Middle Years Advisory Group

Michael E. Addis, PhD

Catherine Cerulli, JD, PhD

Kenneth R. Conner, PsyD, MPH

Marnin J. Heisel, PhD, CPsych

Mark S. Kaplan, DrPH

Monica M. Matthieu, PhD, LCSW

Sally Spencer-Thomas, PsyD

Jeffrey C. Sung, MD

External reviewers

Stan Collins, Anara Guard, Ann Haas, Jarrod Hindman, DeQuincy Lezine, Theresa Ly, Scott Ridgway, and

Eduardo Vega

EDC staff

Avery Belyeu, Lisa Capoccia, Jeannette Hudson, Patricia Konarski, Chris Miara, Jason H. Padgett, Marc Posner,

Laurie Rosenblum, Jerry Reed, and Morton Silverman

Marc Posner served as primary writer for this project. Laurie Rosenblum identied the research literature

summarized in A Review of the Research and was the primary author of Programs and Resources. Meredith

Boginski was responsible for the design of the nal publication. Lisa Capoccia directed the project.

© 2016 Education Development Center, Inc. All rights reserved.

Suggested citation

Suicide Prevention Resource Center. (2016). Preventing suicide among men in the middle years: Recommen-

dations for suicide prevention programs. Waltham, MA: Education Development Center, Inc.

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

4

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This publication may be reproduced and distributed provided SPRC’s citation and website address

(www.sprc.org) and EDC’s copyright information are retained. For additional information about permission

to use or reprint material from this publication, contact [email protected].

Additional copies of this publication can be downloaded from: http://www.sprc.org/resources-programs/prevent-

ing-suicide-men-middle-years

The people depicted in the photographs in this publication are models and used for illustrative purposes only.

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

5

INTRODUCTION

Although men in the middle years (MIMY)—that is, men 35–64 years of age—represent 19

percent of the population of the United States, they account for 40 percent of the suicides in this

country. The number of men in this age group and their relative representation in the U.S. pop-

ulation are both increasing. If the suicide rate among men ages 35–64 is not reduced, both the

number of men in the middle years who die by suicide and their contribution to the overall suicide

rate in the United States will continue to increase.

Unfortunately, the conclusions reached by a 2003 consensus conference on “Preventing Suicide, Attempted

Suicide, and their Antecedents among Men in the Middle Years of Life” still ring true.

[Men in the middle years of life] generally have received the least attention from many of those who are

committed to developing methods of prevention and clinical intervention. Any prevention effort that seeks

to develop a high level of effectiveness must give careful attention to those approaches that “capture” large

segments of the general population, as well as those who carry especially high risk. Men in the middle years,

in particular, will need to be a principal target. (Caine, 2003)

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years: Recommendations for Suicide Prevention Programs is the

nal report of a project that explored the causes of suicide among men ages 35–64 in the United States as well

as what can be done to alleviate the toll that suicide takes on these men and their families, friends, and commu-

nities. The creation of this publication was informed by the following:

ñ A review of the research on suicide among men 35–64 years of age, focusing on research conducted

in the United States and other Western developed countries. It was often necessary to use data or research

that dened “middle years” somewhat differently than our target group of 35–64 years.

ñ Extensive discussions by an advisory group of experts on suicide among men.

ñ Reviews of drafts by the advisory group, other experts, state suicide prevention coordinators, persons with

lived experience, and others.

ñ Initial queries to participants in the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention’s People in the Middle

Years short-term assessment “tiger team” and a survey about existing programs and activities sent to state

suicide prevention planners, selected tribal program planners, and members of the Methamphetamine and

Suicide Prevention Initiative Behavioral Health LISTSERV.

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

6

INTRODUCTION

This publication was created to help state and community suicide prevention programs design and implement

projects to prevent suicide among men in the middle years. These could include programs operated by states,

counties, municipalities, tribal entities, coalitions, and nongovernmental organizations (hereafter referred to

as “state and community suicide prevention programs”). In most cases, such programs will work with other

organizations, agencies, and professionals to achieve the goal of reducing suicide among MIMY. We hope that

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years: Recommendations for Suicide Prevention Programs will

also be of use to these partners, as well as anyone else interested in the health and well-being of men.

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years: Recommendations for Suicide Prevention Programs is

divided into four sections:

Section 1: Understanding Suicide among Men in the Middle Years: Key Points is a distillation of the con-

clusions drawn from our review of the research and informed by input from the advisory group and other

experts.

Section 2: Recommendations for Suicide Prevention Programs provides guidance for state and community

suicide prevention programs. The recommendations were based on the research review and input from the

advisory group and reviewers.

Section 3: A Review of the Research on Suicide among Men in the Middle Years is based on the current

research and data.

Section 4: Programs and Resources is an annotated list of programs and resources that can be used to

implement activities supporting the Recommendations. Some of these programs and resources were de-

signed for use with MIMY. Others were intended for a broader population but have been used with MIMY.

Few have been evaluated.

SECTION 1

Understanding Suicide among

Men in the Middle Years: Key Points

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

8

SECTION 1: Understanding Suicide among Men in the Middle Years: Key Points

These 16 key points represent our conclusions about the scope, patterns, and broader implications of the prob-

lem of suicide among men in the middle years (MIMY). We hope these key points will accomplish the following:

ñ Provide the rationale for the Recommendations for Suicide Prevention Programs

ñ Highlight the role of the partners whose collaboration is essential to implementing the recommendations

ñ Educate and inform staff, collaborators, and the public about suicide among MIMY

1

Much of the increase in suicide in the United States since 1999 can be attributed to an increase in

suicides by men in the 35–64 age group (i.e., men in the middle years).

Men in this age group:

ñ Die by suicide at a substantially higher rate than either women or younger men

ñ Make up more than one half of the male population and approximately one quarter of the total population

of the United States

ñ Will continue to comprise a signicant proportion of the U.S. population for at least the next 25 years

ñ Are not likely to “age out” of risk, as the suicide rate among men ages 65 and older is higher than that of

men ages 35–64

Reducing the overall suicide rate of the United States requires making a substantial reduction in the suicide

rate among men 35–64 years of age.

2

Suicide attempts and ideation have a profound impact on men in the middle years.

Suicide attempts and ideation affect the emotional lives of millions of men and take a toll on their well-being

and their families.

3

The major risk factors for suicide that affect the general population also affect men in the middle years.

These risk factors include mental disorders, alcohol and drug abuse, lack of access to effective behavioral

health services, and access to lethal means.

4

Cultural expectations about masculine identity and behavior can contribute to suicide risk among

men in the middle years.

These expectations can amplify risk factors as well as reduce the effectiveness of interventions that fail to

consider how MIMY think about themselves and their relationships to families, peers, and caregivers. These

cultural expectations include the following characteristics:

ñ Being independent and competent (and thus not seeking help from others)

ñ Concealing emotions (especially emotions that imply vulnerability or helplessness)

ñ Being the family “breadwinner”—an identity that is challenged when a man is unable to provide for his

family (e.g., because he has lost his job)

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

9

SECTION 1: Understanding Suicide among Men in the Middle Years: Key Points

5

Men receive less behavioral health treatment than women even though mental and substance abuse

disorders—especially depression—are major risk factors for suicide among men.

Explanations of why men receive less behavioral health treatment than women include (a) a reluctance among

men to recognize or acknowledge that they could benet from behavioral health services as well as to seek

and accept these services, (b) the failure of clinicians to recognize depression in men and refer them to the

appropriate care (which may result from the fact that depression screening tools are largely developed using

female samples), (c) male perception that behavioral health services are not effective, and (d) the actual and

perceived shame and prejudice that can be related to behavioral health diagnoses and treatment.

6

There are questions about whether clinical interventions targeting suicide risk and related mental

health disorders are as effective for men as for women.

Many clinical interventions were developed and evaluated using research subject groups that were solely or

primarily female. Thus, the evaluations could not determine if these interventions are effective for men. Some

sex-specic analyses of evaluation data of programs designed to reduce suicidal behavior have revealed that

their success is entirely based on their effect on women.

7

Alcohol plays a larger role in suicidal behaviors among men than women.

The role of alcohol in suicide includes both (a) a relationship between sustained alcohol abuse (i.e., alcohol

use disorders) and suicide and (b) the immediate effects of alcohol (i.e., intoxication) on critical thinking and

impulsivity.

8

Firearms play a large role in suicide among men in the middle years.

In 2014, 52 percent of suicides among men 35–64 years of age involved rearms (compared to 32 percent

among women in this age group).

9

Men in the middle years who have employment, nancial, and/or legal problems are at higher risk

for suicide than women or younger men facing those issues.

Suicides associated with external circumstances, such as employment, nancial, or legal problems are more

common among MIMY than among women in the middle years. The risk of suicide among adult men—and es-

pecially among MIMY who are closer to retirement—increases during economic downturns. Suicides associat-

ed with external circumstances are less likely to be preceded by a history of suicide attempts and ideation than

are suicides associated with personal circumstances (e.g., mental disorders) or interpersonal circumstances

(e.g., divorce).

q

Intimate partner problems and domestic violence are associated with suicide risk among MIMY.

Men 35–64 years of age appear to be at greater risk of suicide associated with intimate partner problems than

women. Divorce, loss of custody of children, and other relationship issues have the potential to trigger suicides

of men in this age group. MIMY who perpetrate intimate partner violence are also at increased risk of suicide.

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

10

SECTION 1: Understanding Suicide among Men in the Middle Years: Key Points

w

Men in lower income groups are at greater risk for suicide than men in higher income groups.

Although the data on the relationship of income and wealth to suicide is limited, research using educational

attainment and occupational skill level suggests that suicide risk is higher among people with limited nancial

resources. MIMY in lower income groups are also disproportionately affected by other risk factors for suicide

(e.g., chronic disease and disability and lack of access to effective health and behavioral health care).

e

Men in the middle years who are involved with the criminal justice system are at higher risk for

suicidal behaviors than other men.

More than 40 percent of men in the 35–64 age group who reported attempting suicide also reported being

arrested and booked for a criminal offense in the past 12 months. The relationship between suicide risk and

involvement with the criminal justice system may be due to the fact that (a) men from lower income groups and

men with mental disorders and/or alcohol or drug use disorders are disproportionately involved with the crimi-

nal justice system and (b) the stress and shame of being involved with the criminal justice system can in and of

itself contribute to suicide risk.

r

Veterans in the middle years (a population that is largely male) have a higher suicide rate than their

peers who have not served in the military.

This phenomenon may be related to (a) trauma associated with combat, (b) interpersonal issues associated

with deployment and re-entry into civilian life, and (c) the demographics of the all-volunteer army.

t

Gay, bisexual, and transgender men in the middle years may be more at risk for suicide than other

men of their age.

The research reveals that lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth, and young people who do not conform

to standard gender roles, are much more at risk for suicide attempts than other youth. Because most death

data do not include information about sexual orientation and transgender status, we cannot conclusively prove

that these young people are more at risk of suicide than the general population. There is evidence that the still

considerable social disapproval surrounding sexual orientation can contribute to an increased risk of suicidal

behavior and associated mood disorders among adult GBT men.

y

The research on protective factors is not as robust as the research on risk factors and pathology.

There is limited research on interventions that leverage protective factors to prevent suicide among men in the

middle years. Additional research is also needed on interventions that will help boys, male adolescents, and

young men to develop the resilience that will offer protection against suicide risks they may face when they

reach the middle years.

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

11

SECTION 1: Understanding Suicide among Men in the Middle Years: Key Points

u

It is important to acknowledge the toll that suicide takes among other groups, including women and

men of other ages, even if the absolute numbers of these deaths are much lower than the number

of suicides among men in the middle years.

This is especially true for groups whose behavioral health disparities (including suicide risk) are rooted in his-

torical and/or contemporary patterns of trauma, discrimination, and exclusion and who are in need of effective

and culturally appropriate suicide prevention efforts (e.g., American Indians and Alaska Natives).

SECTION 2

Recommendations for

Suicide Prevention Programs

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

13

SECTION 2: Recommendations for Suicide Prevention Programs

These recommendations outline a framework for the implementation of a comprehensive state or community

effort to prevent suicide among men in the middle years (MIMY). It is virtually impossible to reduce the suicide

rate of the general population without reducing the rate of suicide among MIMY. As a rst step, we suggest that

state and community suicide prevention programs prioritize MIMY as a key target population.

Implementing the Recommendations

Suicide does not have a single cause. Nor does it have a single solution. Effectively preventing suicide requires

a comprehensive set of interventions that address the major factors that put people at risk. Such a comprehen-

sive system can only be created incrementally. The rst step in building this system is creating a strategic plan

informed by the specic scope and patterns of suicide among MIMY in your state or community. This includes

identifying the following:

ñ Populations most at risk

ñ Factors that put these people at risk

ñ Resources that are available for reducing this risk

It is essential that both community and clinical components are included given that both are essential to pre-

venting suicide. This approach is as central to preventing suicide among MIMY as it is to addressing the overall

problem of suicide in a community, a state, or the nation as a whole.

Building a comprehensive suicide prevention program for MIMY includes the following steps:

1. Describe the problem in your state or community, which may differ from that summarized in Understanding

Suicide among Men in the Middle Years: Key Points. These differences can stem from factors such as the

ethnic and income groups represented or the availability of mental health services and lethal means (e.g.,

rearms) among MIMY in your state or community.

2. Identify risk and protective factors. The risk and protective factors for suicide among MIMY are outlined in

the Key Points. An understanding of the specic risk and protective factors in your state or community is

essential to effective prevention.

3. Find appropriate partners. The risk factors affecting MIMY in your state and community, as well as the inter-

ventions that effectively address these risk factors, have implications for the partners you will need.

4. Select, implement, and evaluate interventions. The recommendations can help you select the interventions

that are most appropriate to your needs. A list of tools and other materials that can help you implement the

interventions can be found in the Programs and Resources section of this report. All the resources men-

tioned in the recommendations can be found in that section.

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

14

SECTION 2: Recommendations for Suicide Prevention Programs

This report presents 17 recommendations:

ñ Recommendations 1–3 summarize the principles that should inform all activities to prevent suicide among

MIMY.

ñ Recommendations 4–15 describe how state and community suicide prevention programs can help agencies,

organizations, and professionals that work with MIMY to integrate suicide prevention into their activities

ñ Recommendation 16 addresses policies that can reduce suicides associated with rearms, which represent

52 percent of suicides among MIMY, as well as suicides associated with alcohol use.

ñ Recommendation 17 addresses the need for research on suicide and suicide prevention among MIMY.

The Recommendations

To prevent suicide among MIMY, we recommend the following actions for state and community suicide preven-

tion programs:

1

Revise your state or community suicide prevention plan to ensure that it adequately addresses

suicide among MIMY:

ñ Include data and other information about the problem of suicide among MIMY

ñ Identify and revise objectives and activities that could be enhanced to prevent suicide among MIMY

ñ Include new activities specially designed to prevent suicide among MIMY

2

Develop, implement, and facilitate suicide prevention activities based on an understanding of risk

and protective factors among men in the middle years.

Major risk factors for suicide for MIMY include the following:

ñ Depression and other mental disorders

ñ A history of suicidal behavior, including suicidal ideation and attempts

ñ Alcohol use disorder and intoxication

ñ Access to rearms

ñ Illness or disability, including chronic medical conditions, physical

disability, and/or a new diagnosis of a serious illness

ñ Financial stress, both ongoing (e.g., having a low income/low status

occupation) and immediate (e.g., job loss, foreclosure)

ñ Intimate partner problems, both ongoing (e.g., divorce, separation)

and immediate (e.g., breakup, loss of child custody), and committing

or being the victim of intimate partner violence

The term facilitate is used

in several of the recommen-

dations to refer to a range

of activities, including pro-

viding information, resourc-

es, training, and technical

assistance to agencies,

organizations, and profes-

sionals.

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

15

SECTION 2: Recommendations for Suicide Prevention Programs

ñ Criminal justice system involvement, both long-term (e.g., men who are awaiting adjudication or on pro-

bation) and immediate (e.g., arrest, impending court date, or impending incarceration)

ñ Other stressors that can precipitate suicide, including family and civil court cases

Major protective factors against suicide for MIMY include the following:

ñ Access to effective health and behavioral health care

ñ Social connectedness to individuals, including friends and family, and to community and social institutions

ñ Coping and problem-solving skills

ñ Reasons for living, meaning in life, and purpose in life

3

Incorporate an understanding of cultural expectations about masculine identity and behavior and

how these expectations affect suicide risk. These expectations impact how MIMY:

ñ Cope with problems and stress.

ñ Seek (or fail to seek) help.

ñ Engage with others and accept help. For example, men can be more accepting of help when it is offered

in the context of reciprocity (i.e., in a mutual exchange in which men accept help from others while also

providing help to others).

ñ Express or “mask” (conceal) depression and suicidal ideation as anger, agitation, nonspecic psychologi-

cal distress, or physical ailments (e.g., back pain).

Masculine identity and behavior can differ based on personal characteristics, upbringing, and critical life expe-

riences, including sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, income level, and military service. This identity and these

expectations and experiences also inuence the venues and channels through which MIMY can be reached

with prevention messages (e.g., sporting events, talk radio, and online media).

4

Collaborate with and facilitate efforts by primary health care providers to:

ñ Incorporate into their practice an understanding of (a) how suicide risk and associated mental disor-

ders (e.g., depression) can be masked in MIMY; (b) the relationship between suicide risk and alcohol

and drug use disorders, chronic disease, and disability; and (c) characteristic patterns of coping and

help-seeking behavior among MIMY

ñ Screen and assess MIMY for suicide risk, and, when indicated, refer patients to behavioral health ser-

vices and follow-up to ensure that the patients are receiving behavioral health care

ñ Intervene to keep patients safe using brief interventions (e.g., safety planning that includes teaching men

how to leverage their peer and social support networks and counseling on reducing access to lethal

means, especially rearms) and involving the patient’s family

ñ Enhance coping, problem-solving, and self-management skills among MIMY at risk for suicide using

interventions such as motivational interviewing and problem-solving therapy

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

16

SECTION 2: Recommendations for Suicide Prevention Programs

ñ Provide SBIRT (Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment) to MIMY with alcohol or drug

use disorders

5

Collaborate with and facilitate efforts by emergency departments to:

ñ Incorporate into their practice an understanding of (a) how suicide risk and associated mental disor-

ders (e.g., depression) can be masked in MIMY; (b) the relationship between suicide risk and alcohol

and drug use disorders, chronic disease, and disability; and (c) characteristic patterns of coping and

help-seeking behavior among MIMY

ñ Screen and assess MIMY for suicide risk if there is any indication

that such risk is present

ñ Screen and assess all intoxicated MIMY presenting in emergency

departments for suicide risk

ñ Provide SBIRT (Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treat-

ment) to MIMY with alcohol or drug use disorders

ñ Implement protocols for responding to suicide risk in patients, includ-

ing using brief interventions (e.g., safety planning that includes teach-

ing men how to leverage their peer and social support networks and

counseling on reducing access to lethal means, especially rearms);

involving the patient’s family or friends; linking the patient to outpa-

tient behavioral health treatment; and hospitalization

ñ Facilitate care transitions, including rapid referral to behavioral health

services

ñ Provide follow-up to discharged patients with brief communications

(e.g., postcards, e-mails, or texts) to facilitate adherence to discharge

plan and demonstrate a continued interest in patient well-being (i.e.,

social connectedness)

ñ Implement the guidance included in Caring for Adult Patients with Suicide Risk: A Consensus Guide for

Emergency Departments

6

Collaborate with and facilitate efforts by behavioral health services to:

ñ Incorporate into their practice an understanding of (a) how suicide risk and associated mental disor-

ders (e.g., depression) can be masked in MIMY; (b) the relationship between suicide risk and alcohol

and drug use disorders, chronic disease, and disability; and (c) characteristic patterns of coping and

help-seeking behavior among MIMY

ñ Screen MIMY for suicide risk during entry to care and during the course of care if there are indications of

potential risk; provide more in-depth assessment for men who screen positive or when risk is suspected

The Zero Suicide Toolkit

includes resources that can

help you implement many

of the recommendations for

primary care and behavioral

health care systems and

emergency departments.

The toolkit includes sec-

tions on training options,

suicide screening and risk

formulation, evidence-based

treatments (including thera-

pies), and care transitions.

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

17

SECTION 2: Recommendations for Suicide Prevention Programs

ñ Use strategies to keep men safe, including brief interventions (e.g., safety planning that includes teaching

men how to leverage their peer and social support networks and counseling on reducing access to lethal

means, especially rearms) involving the patient’s family, medication, or hospitalization

ñ Use psychotherapies that directly address suicide risk and enhance coping, problem-solving, and

self-management skills

ñ Positively engage patients in their own care

ñ Explore alternative settings and methods for bringing behavioral health services to men (e.g., workplaces,

telepsychiatry)

7

Collaborate with crisis centers to educate staff about:

ñ How suicide risk and associated mental disorders (e.g., depression) present or can be masked among

MIMY

ñ Screening and assessing MIMY who have been diagnosed with depression, other mental disorders, or

an alcohol or drug use disorder for suicide risk

ñ Keeping MIMY at risk safe by using strategies including brief interventions (e.g., safety planning that in-

cludes teaching men how to leverage their peer and social support networks and counseling on reducing

access to lethal means, especially rearms) and involving the patient’s family

8

Collaborate with and facilitate efforts by agencies and organizations that work to prevent and treat

alcohol abuse to:

ñ Incorporate into their practice an understanding of (a) the relationship between alcohol use disorder,

intoxication, and suicide risk, (b) how suicide risk and associated mental disorders (e.g., depression) can

be masked in MIMY, and (c) characteristic patterns of coping and help-seeking behavior among MIMY

ñ Train staff to recognize, assess, and manage suicide risk and associated mental disorders (e.g., depres-

sion) among their clients

ñ Incorporate suicide prevention-specic treatment and practices into their programs based on the recom-

mendations of SAMHSA’s Addressing Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors in Substance Abuse Treatment:

A Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP 50)

ñ Facilitate transitions to mental health care when appropriate

ñ Include information on the relationship of alcohol and suicide among MIMY in resources designed to

inform state and local policies to reduce alcohol use disorders and other forms of alcohol misuse (e.g.,

binge drinking). Such information can be found under A Review of the Research on Suicide among Men

in the Middle Years (below).

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

18

SECTION 2: Recommendations for Suicide Prevention Programs

9

Collaborate with organizations and businesses that serve or represent rearm owners and users

(including rearm retailers, rearm safety instructors, ring ranges, and gun and hunting clubs) to

create a culture of safety by:

ñ Providing them with information on the role of rearms in suicide and how suicide can be prevented

ñ Providing gatekeeper training to rearm owners, staff of rearm-related businesses, and members of gun

and hunting clubs and other rearms-related organizations

ñ Training rearm retailers to identify and avoid or postpone sales to customers who may be at risk for

suicide

ñ Incorporating material on lethal means reduction into rearm safety training

q

Facilitate efforts by criminal justice, law enforcement, and correctional agencies to:

ñ Establish procedures and provide training that will help criminal justice, law enforcement, and corrections

ofcers safely and effectively respond to people at risk for suicide. This training should include informa-

tion about the association between suicide risk and (1) involvement in the criminal justice system and (2)

mental health and substance abuse disorders.

ñ Utilize the Sequential Intercept Model (SIM) to prevent people with mental disorders and alcohol and

drug use disorders from entering or moving deeper into the criminal justice system by diverting them

to community-based services when appropriate, providing behavioral health services in correctional

facilities, and providing effective reentry transitional programs for people being discharged from

correctional facilities

ñ Screen MIMY for suicide risk during intake in jails and prisons and implement best practices for address-

ing this risk (e.g., monitoring inmates and eliminating items and physical features from cells that could be

used for self-harm, such as those that could be used for hanging)

ñ Provide behavioral health services to MIMY in jails and prisons, including treatment for depression and

other mental disorders and alcohol and drug use disorders

w

Help agencies, programs, and professionals that work with men having nancial, legal, or relation-

ship problems (including civil court issues) to identify and refer those who may be at risk of suicide.

These include agencies and programs serving MIMY who have:

ñ Financial problems – These agencies, programs, and professionals would include but not be limited to

affordable housing agencies, job training programs, unemployment services, employee assistance pro-

grams, human resource ofces, public defenders, nancial advisors, and bankruptcy attorneys.

ñ Intimate partner problems – These agencies, programs, and professionals would include divorce attor-

neys, family law attorneys, marriage counselors, and programs that counsel men involved in domestic

violence.

ñ Legal problems – These agencies, programs, and professionals might include family, civil, and bankruptcy

courts; attorneys; mediation services; and legal aid law clinics.

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

19

SECTION 2: Recommendations for Suicide Prevention Programs

e

Help workplaces that employ substantial numbers of men in the middle years implement programs to:

ñ Teach employees how to identify and respond to coworkers who may be at risk for suicide or experienc-

ing a mental health crisis

ñ Establish postvention procedures for responding to a suicide by a worker (whether or not the death

occurs in the workplace)

ñ Provide specialized suicide prevention training for human resources staff and/or employee assistance

providers for employees who are being terminated or laid off

ñ Implement suicide prevention activities such as those described in the National Action Alliance for

Suicide Prevention’s Comprehensive Blueprint for Workplace Suicide Prevention

ñ Foster a supportive workplace environment free from attitudes and discrimination that might deter people

from seeking help for stress and mental health issues

r

Work with television and radio stations, newspapers and magazines, and online news sites to

develop and implement outreach and social norms campaigns to:

ñ Teach men how to recognize and seek help for suicide risk and associated mental disorders (e.g.,

depression) and alcohol and drug disorders for themselves and their peers

ñ Teach family and friends to identify MIMY at risk of suicide and how to encourage them to seek care

ñ Promote help seeking as a social norm for men

ñ Emphasize reaching men who are socially isolated and/or may not interact with health care providers

t

Help organizations and agencies that address suicide risk among men in the middle years

implement activities that strengthen protective factors.

These organizations and agencies (described in Recommendations 4–12 above) could, for example, create

projects that teach coping skills to MIMY who are unemployed, separated, divorced, widowed, in recovery,

disabled, or chronically ill.

y

Support the creation of community-based groups that create social connectedness and enhance

self-worth, meaning in life, and a sense of purpose among men in the middle years.

For example, identify natural helpers or community leaders who could help organize programs that target and

promote protective factors among MIMY with common backgrounds (e.g., veterans or American Indians) or

risk factors (e.g., unemployment, alcohol or drug abuse).

u

Promote awareness of policies that have been shown to be associated with a reduction in suicide,

including the following:

ñ Requiring permits to purchase handguns, handgun registration, and licenses to own handguns

ñ Requiring background checks and waiting periods prior to completing a handgun purchase

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

20

SECTION 2: Recommendations for Suicide Prevention Programs

ñ Requiring privately owned handguns to be safely stored

ñ Restricting the open carrying of handguns

ñ Restricting the number of liquor licenses available in geographic areas such as neighborhoods, munici-

palities, or counties to limit the density of bars and retail liquor outlets

i

Researchers should improve the understanding of risk and protective factors and help develop

effective interventions for suicide among men in the middle years by:

ñ Reporting data by sex and age group and, if possible, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and sexual

orientation

ñ Working with state and community suicide prevention programs to evaluate their efforts

ñ Clarifying the following issues:

1.

What factors contribute to suicide risk among MIMY? How can these factors be reduced?

2. What factors protect MIMY against suicide risk, and how can this protection be strengthened? What

programs can effectively increase these protective factors among MIMY?

3.

How can suicide prevention programs more effectively prevent suicide among MIMY by responding to

their cultural and behavioral expectations, their learning styles, and the ways in which they characteris-

tically seek and accept help?

4.

How can screening, assessment, and treatment of suicide risk and associated mental disorders be

made more effective for MIMY?

5.

How can help seeking and treatment engagement be enhanced for MIMY, and what roles can family,

peers, and the media play in these efforts?

6.

What are the differences in the patterns of suicide and suicide attempts among MIMY based on

(1) age—specically between younger (35–49 years of age) and older (50–64 years of age) MIMY,

(2) income level, and (3) sexual orientation and gender identity? What are the implications of these

differences for designing effective interventions for men in these age groups?

7.

What specic risk and protective factors are at work among groups of MIMY that may be at particular-

ly high risk (e.g., veterans, GBT men)?

8.

Does the current rate of suicide among MIMY represent a temporary cohort effect or a long-term pat-

tern? What implications does this have for planning and implementing suicide prevention programs in

the future?

9.

What can be done earlier in men’s lives (including childhood and adolescence) that will promote resil-

ience and protection against suicide when they enter the middle years?

SECTION 3

A Review of the Research on Suicide

among Men in the Middle Years

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

22

SECTION 3: A Review of the Research on Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

This review is based on the published research and surveillance data as well as on an analysis of data from

SAMHSA’s National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). The review focused on research on men 35–64

years of age conducted in the United States and other Western developed countries. It was often necessary to

use data or research that dened middle years somewhat differently than our target group of 35–64 years. We

did not review (1) interventions targeting boys, adolescents, or younger men that might reduce risk or protect

against the onset of suicidal behaviors as these men age or (2) interventions targeting men older than 64. How-

ever, we acknowledge the role of such interventions in comprehensive efforts to prevent suicide.

Scope and Patterns

Men in the middle years (MIMY) disproportionately die by suicide. In 2014, men 35–64 years of age represent-

ed 19 percent of the population of the United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014), but they accounted for 40

percent of suicides (CDC, 2014).

About half of the American population is male. As of 2014, 39.4 percent of the total U.S. population was 35 to

64 years of age (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014). The number of people in the middle years, as well as the propor-

tion of the U.S. population that is in this age group, is increasing.

ñ The number of people ages 45–64 years in the United States in the years 2000–2010 increased by 31.5

percent (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011).

ñ The median age of the U.S. population increased from 29.5 years in 1960 to 37.2 years in 2010 (U.S. Cen-

sus Bureau, 2011).

Suicidal Behavior among Men in the Middle Years

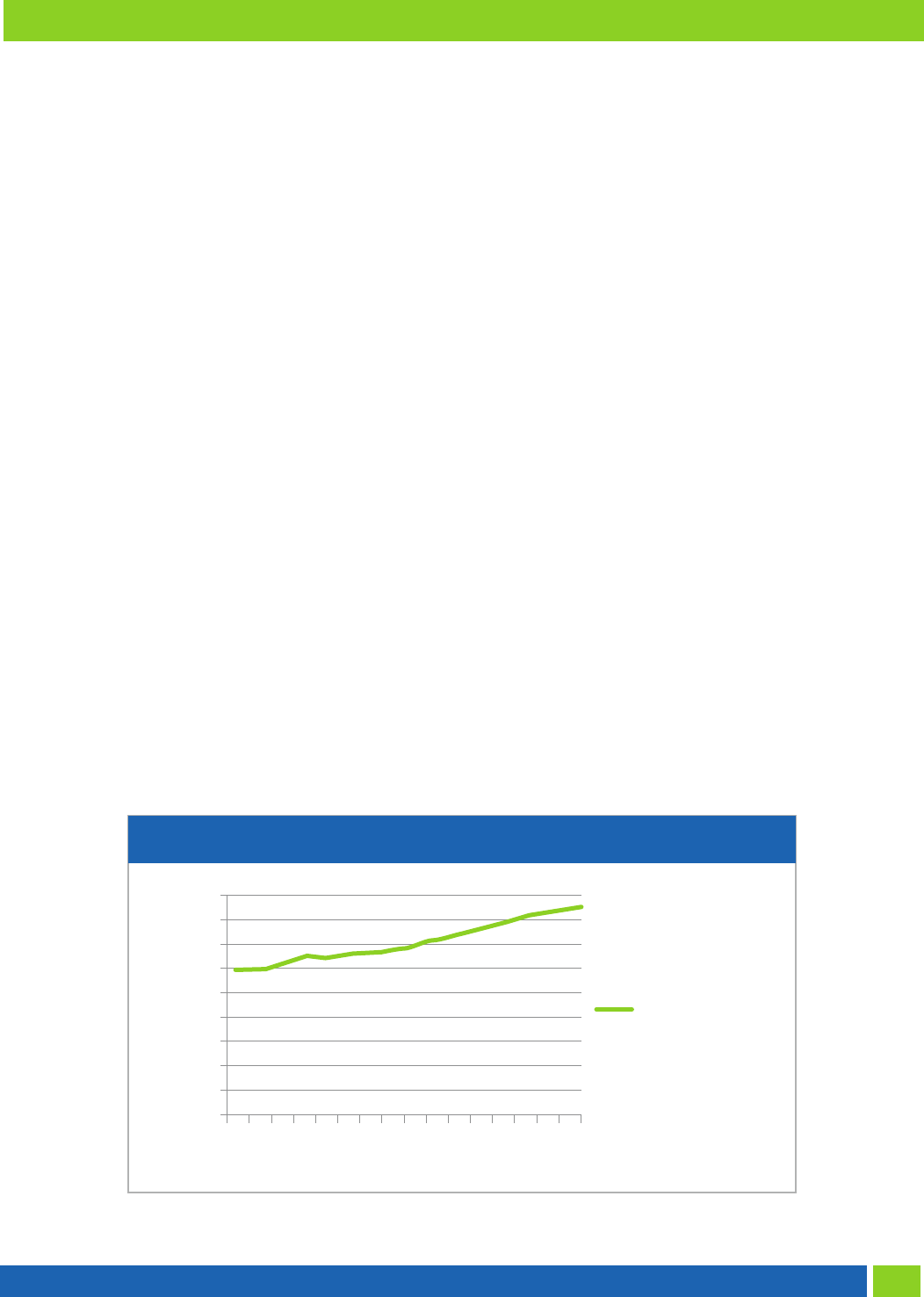

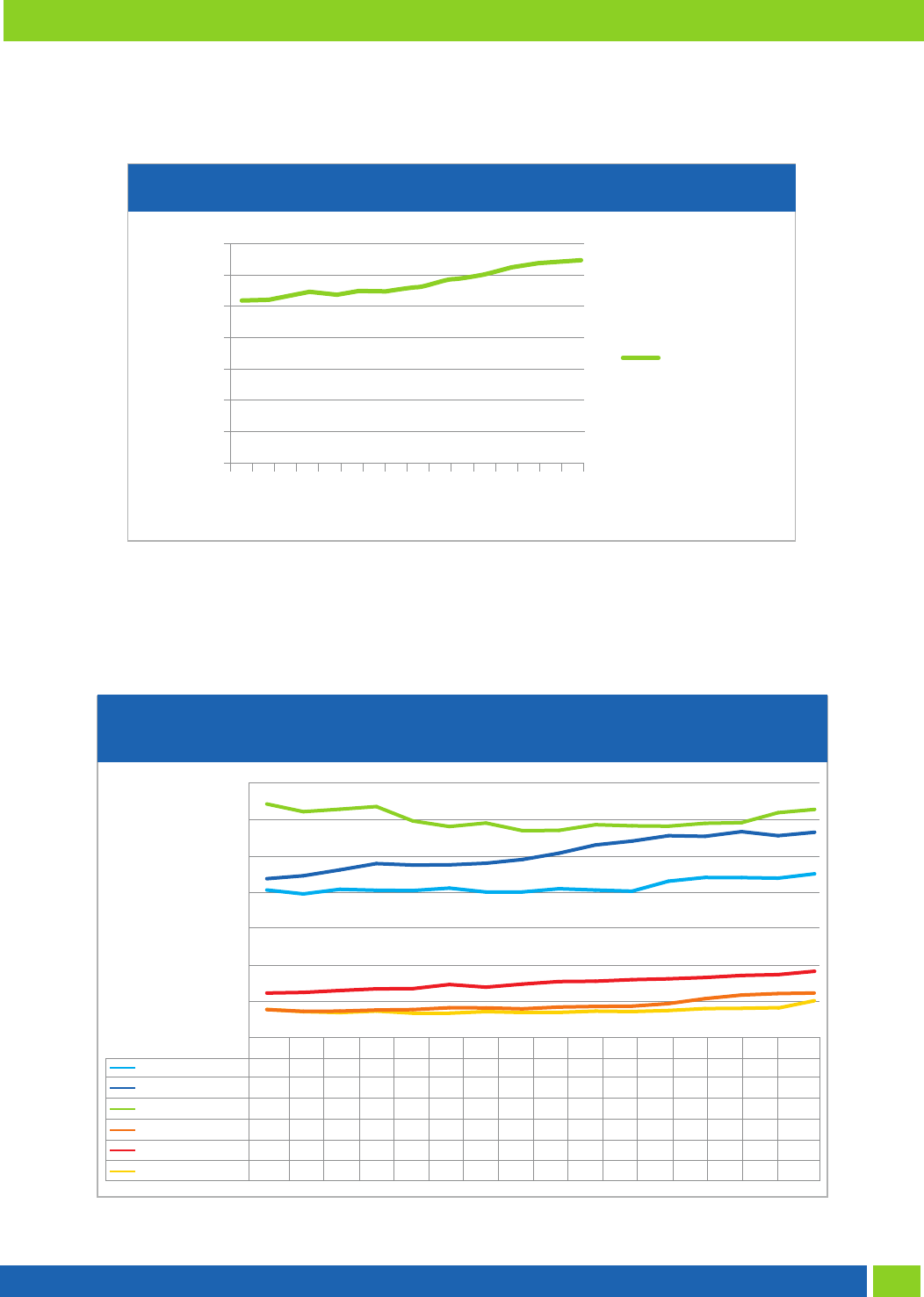

The suicide rate and the absolute number of suicides in the United States have continually increased since

1999. The number of suicides in the United States rose from 29,350 in 1999 to 42,773 in 2014 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Suicide Deaths in the U.S. by Year

Number of Suicide Deaths in the U.S. by Year, 1999–2014

45,000

40,000

35,000

30,000

25,000

20,000

15,000

10,000

5,000

0

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

Number of Suicide

Deaths

Source: Data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014).

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

23

SECTION 3: A Review of the Research on Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

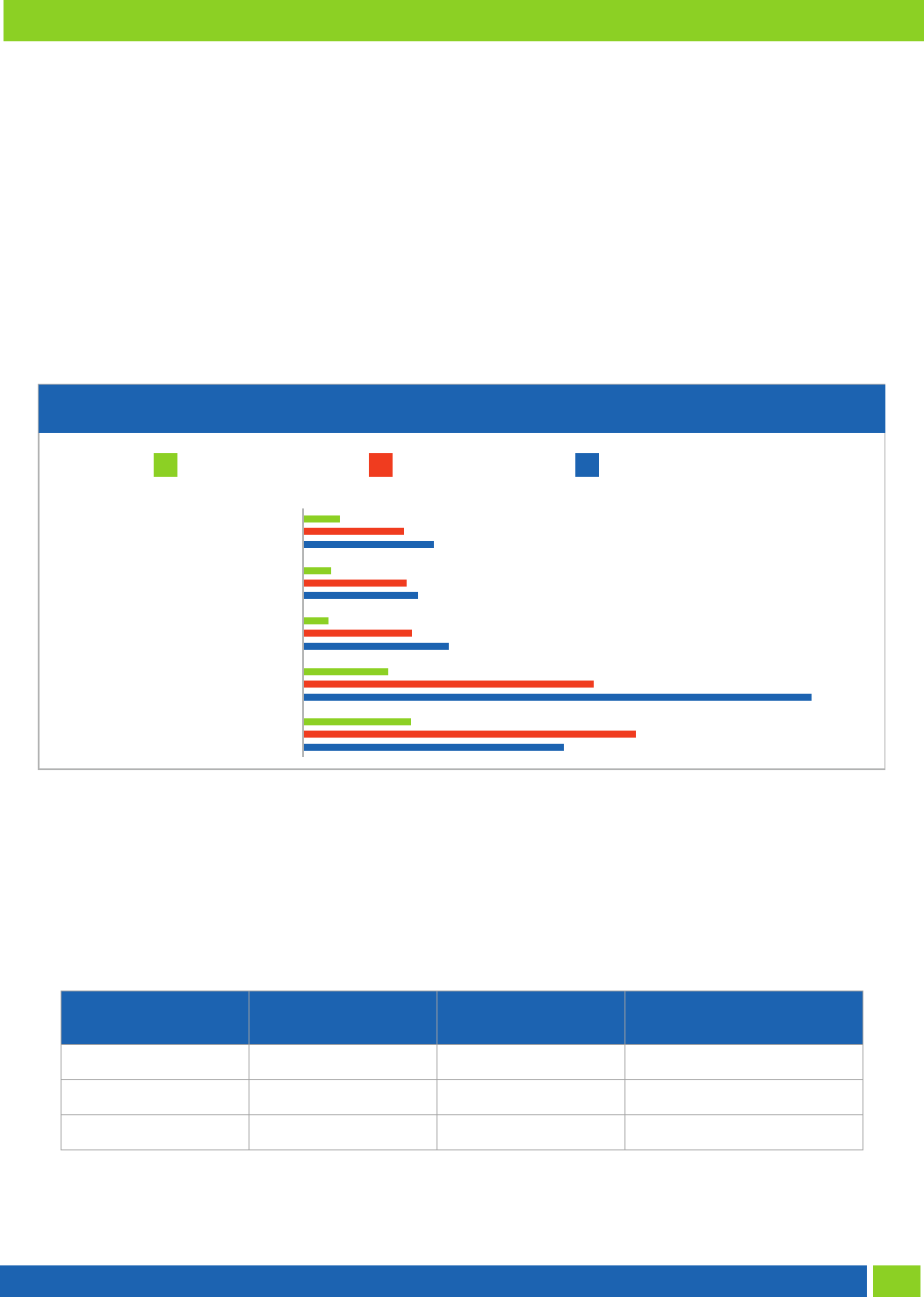

The suicide rate in the United States increased from 10.48/100,000 in 1999 to 13.41/100,000 in 2014 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Suicide Rate in the U.S. by Year

Suicide Rate per 100,000 in the U.S. by Year, 1999–2014

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

Crude Rate

Source: Data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014).

Much of the growth in the suicide rate and the number of suicides in the United States since 1999 can be

attributed to an increase in suicides by men 35–64 years of age (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Crude Suicide Rates in the U.S. by Age and Sex

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Rate per 100,000

Men Ages 18-34

Women Ages 18-34

Women Ages 35-64

Women Ages 65+

Men Ages 35-64

Men Ages 65+

1999

20.39

21.5

32.17

4.07

6.18

4.34

2000

19.83

21.92

31.07

3.82

6.27

4.03

2001

20.49

22.76

31.42

3.85

6.54

3.89

2002

20.35

23.66

31.8

4.01

6.78

4.11

2003

20.31

23.45

29.74

4.07

6.81

3.81

2004

20.66

23.48

28.95

4.33

7. 4

3.81

2005

20.1

23.71

29.45

4.31

7.02

4.03

2006

20.11

24.24

28.36

4.18

7. 4 6

3.91

2007

20.57

25.14

28.4

4.43

7.82

3.92

2008

20.38

26.32

29.21

4.52

7. 87

4.1

2009

20.22

26.87

29.05

4.56

8.09

4.04

2010

21.65

27.6 4

29

4.92

8.21

4.19

2011

22.18

27.55

29.41

5.25

8.4

4.46

2012

22.16

28.22

29.5

5.36

8.69

4.5

2013

22.08

27.6 4

30.93

5.57

8.81

4.59

2014

22.70

28.13

31.39

5.65

9.29

5.04

Crude Suicide Rates per 100,000 in the U.S.

by Age and Sex, 1999-2014

Source: Data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014).

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

24

SECTION 3: A Review of the Research on Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

The largest increase in the suicide rate during the years 1999–2014 was among people 35–64 years of age.

Although the increase in the suicide rate for women 35–64 was somewhat higher than that for men in that age

group, the suicide rate for MIMY continues to be substantially higher than that for women in the middle years

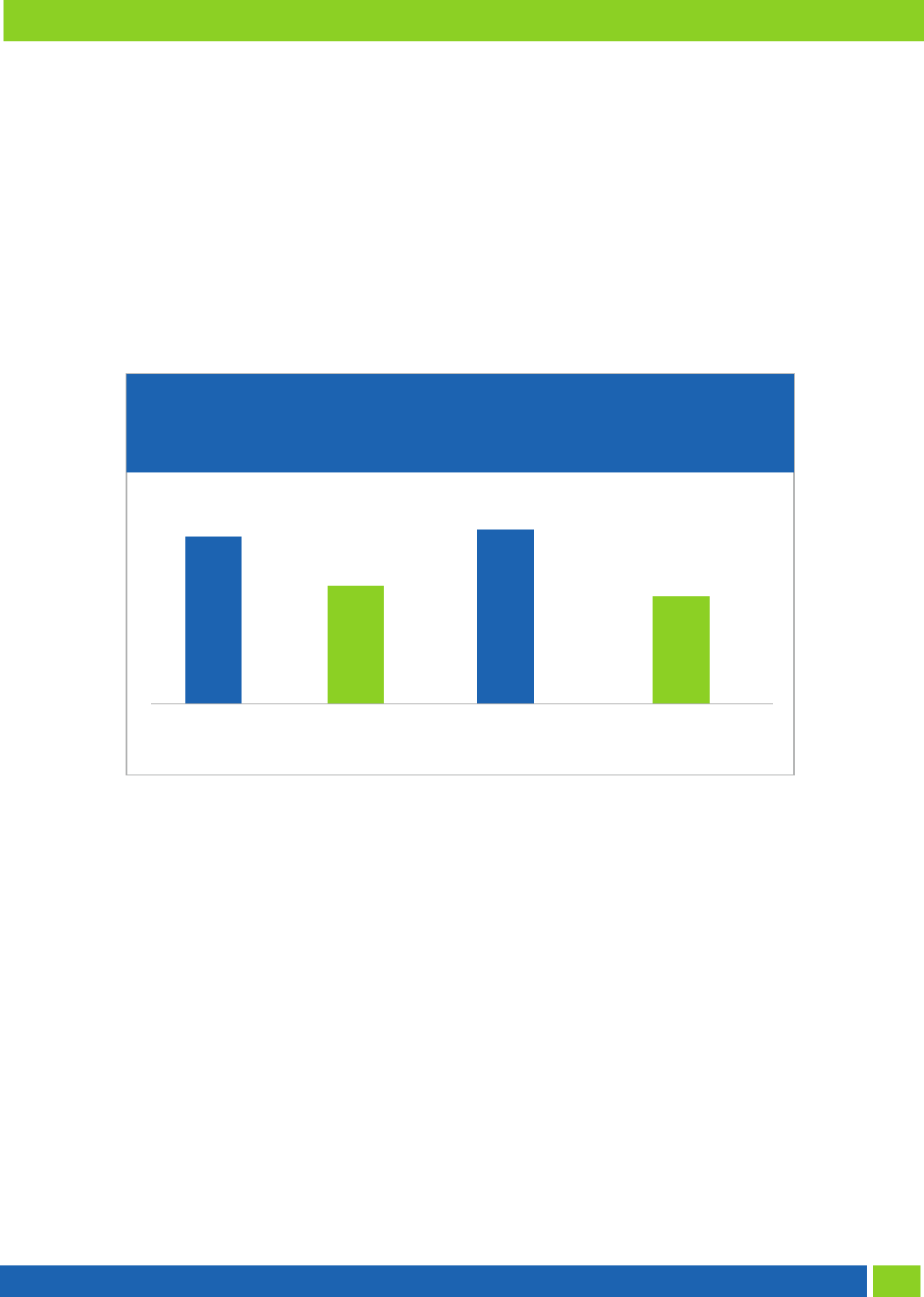

(Figure 3). Men ages 35–64 represent a disproportional percentage of suicides in this country (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Suicide in the United States, 2014

Suicide in the United States, 2014

Men 35-64 Men 0-34 & 65+ Women 0-65+

Source: Data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014).

The suicide rate of men rises with age, and suicide rates among men are higher than those among women in

every age group (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Suicide Rates in the U.S. by Age and Sex, 2014

Suicide Rates in the U.S by Age and Sex, 2014

Men Women

18-34

22.70

5.65

35-64

25.13

9.29

65+

31.39

5.04

Source: Data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014).

40.06%

59.94%

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

25

SECTION 3: A Review of the Research on Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

According to the NSDUH, an average of 0.4 percent of men 35–64 years of age made a suicide attempt during the

years 2008–2013. This was the same as the percentage of women 35–64 who made an attempt, but lower than

the percentage of men 18–34 years of age (Table 1). Using U.S. Census data, we can estimate that in 2013:

ñ 242,779 men 35–64 years of age attempted suicide

ñ 2,306,402 men 35–64 years of age had serious thoughts of suicide

Table 1. Average Percentages of Attempts and Serious Thoughts of Suicide

in the Past 12 Months by Sex and Age Group, 2008–2013

Sex/Age Attempts Serious Thoughts of Suicide

Men 18-34 0.7% 4.9%

Men 35-64 0.4% 3.4%

Women 35-64 0.4% 3.7%

Source: Data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2008-2013, Substance Abuse Mental Health Services

Administration (2013).

The prevalence of suicide attempts is higher than the rate of individuals who make attempts because some indi-

viduals attempt suicide more than once over the course of a year.

Although men and women in the middle years attempt suicide at about the same rate (400/100,000 as indicated

in the previous table), there is a difference in the relationship of attempts to suicides based on sex. Hempstead

and Phillips (2015) found that 36.7 percent of women in the 40–64 age group who died by suicide had made at

least one attempt prior to the attempt that resulted in their death. Only 18.9 percent of the men in that age group

who died by suicide had made a prior attempt. Hempstead and Phillips suggest that this may be at least partially

explained by the following facts:

ñ Suicides associated with external circumstances (e.g., job or legal problems) are less likely to be preceded

by a nonfatal suicide attempt than are suicides associated with internal circumstances (e.g., mental health

conditions) or interpersonal problems (e.g., divorce).

ñ Suicides by men in this age group are signicantly more likely to be associated with external circumstances

than suicides by men in other age groups or women.

The relationship between suicide attempts and suicide among MIMY may also be at least partially attributed to

the fact that men in this age group tend to use more lethal means to harm themselves (primarily guns), and thus

they are less likely to survive their initial suicide attempt than are women. The percentages of men and women

in the middle years who received medical attention after a suicide attempt were similar (67 percent men; 72.7

percent women). Both of these percentages were substantially higher than that of people in the 18–34 age

group (47 percent men; 46.3 percent women). Non-fatal attempts by men in the 35–64 age group result in

more severe injuries than those by younger men (SAMHSA, 2013).

An analysis of pooled data from the NSDUH and the National Vital Statistics System (Han et al., 2016) found that

7.6 percent of men 45 years and older who attempt suicide in the United States during a 12-month period actually

die by suicide. This includes both men who die on their rst attempt and men who died on a subsequent attempt

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

26

SECTION 3: A Review of the Research on Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

in this 12-month period. This rate was signicantly higher than the corresponding rates for women 45 years and

older (2.6 percent), men ages 26–44 (5.1 percent), and men ages 18–25 years (1.9 percent). This study also

revealed that suicide rates among people who attempt suicide tend to increase with age and decrease with

educational attainment.

Race/Ethnicity

Men in the 35–64 age group have substantially higher suicide rates than women in that age group across the

racial/ethnic spectrum. The suicide rate among white men 35–64 years of age is higher than that of younger

white men 18–34, which is not the case in other racial/ethnic groups (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Suicide Rates by Racial/Ethnic Group, 2014

Suicide Rates per 100,000 by Racial/Ethnic Group, 2014

Women Ages 35-64 Men ages 18-34Men ages 35-64

Asian/Pacific Islander

Hispanic

Black

American Indian/Alaskan Native

White

12.30

35.91

25.55

8.52

30.54

47.58

2.83

11.20

15.70

3.20

12.32

13.25

3.63

9.14

12.94

Source: Data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014).

White men account for the majority of suicide attempts by men in the United States. However, suicide attempts

by black and Hispanic men 35–64 years of age are disproportionately higher than their representation among

males in these ethnic groups (Table 2).

Table 2. Percentage of Men Who Attempted Suicide in the Past 12 Months by Racial/Ethnic

Group and Percentage of the Male Population Ages 35–64 by Racial Ethnic Group, 2008-2013

Racial/Ethnic Group Men 18–34 Men 35–64 Percentage of Male Population,

Ages 35–64 Years

White (non-Hispanic) 58.3% 55.7% 69%

Black (non-Hispanic) 15.3% 19.9% 11%

Hispanic 19.2% 17.9% 12%

Sources: Attempt data from National Survey of Drug Use and Health, 2008–2013, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2013);

percentage of male population data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014).

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

27

SECTION 3: A Review of the Research on Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

An accurate picture of suicide attempts among American Indians/Alaska Natives and Asians and Pacic Island-

ers could not be calculated using NSDUH data because of the small number of members of these groups who

participated in the survey.

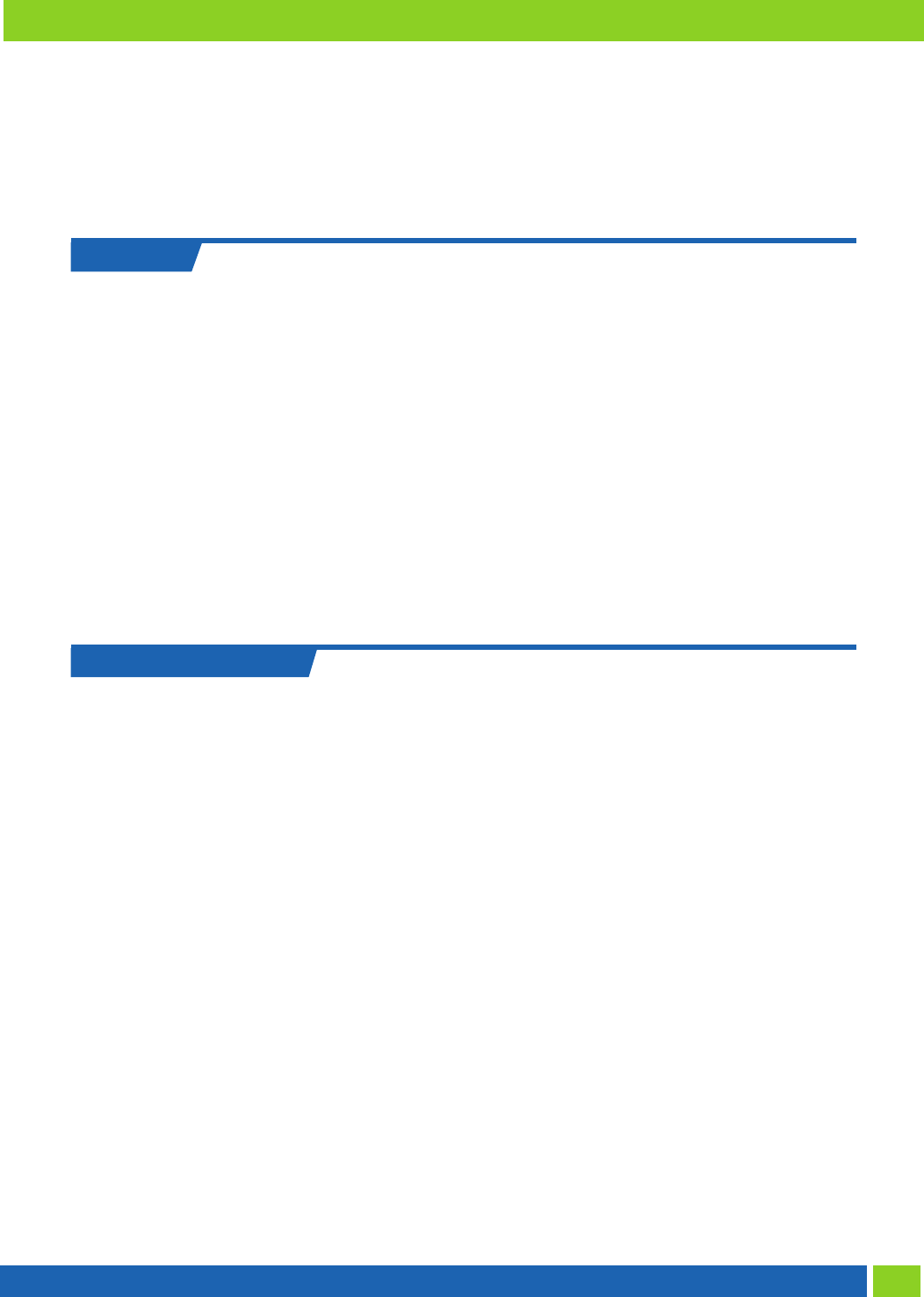

Men in the Criminal Justice System

The data reveal that 40.6 percent of men in the 35–64 age group who had attempted suicide in the past 12

months (and 44.2 percent of those who had serious thoughts of suicide) had been arrested and booked for a

criminal offense during that period (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Arrests and Bookings among People Ages 35–64 Reporting Suicidal Behaviors, by Sex

Arrests & Bookings (Past 12 Months) among

People 35-64 Years of Age Reporting Suicidal

Behaviors (Past 12 Months) by Sex (2008-2013)

Men

Attempts

Women

Attempts

Men Serious

Thoughts

Women Serious

Thoughts

40.60%

44.20%

29.00%

23.20%

Source: Data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2008-2013, Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration (2013).

Hempstead and Phillips (2015) also found that a signicantly higher percentage of suicides among men 40–64

years of age were associated with criminal problems than were suicides of women (11.5 percent versus 3.8 percent).

The bulk of arrests in the United States are related to crimes that involve drugs and alcohol (U.S. Dept. of Jus-

tice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2012), which are behaviors associated with suicide risk. The arrest rate

for men and the male arrest rate for crimes related to drugs and alcohol are about three to four times those of

women (Snyder, 2012).

Schiff et al. (2015) analyzed National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) data for men ages 35–64 who

died by suicide and had experienced a recent crisis (such as a divorce or arrest). The study excluded men with

a known history of mental health or substance abuse problems so that the factors putting men at risk for suicide

independent of these behavioral health issues could be identied. About half of the men in the sample had ex-

perienced criminal and/or legal problems. About 20 percent of the suicides of men with criminal/legal problems

showed signs of premeditation. Men who did not have criminal/legal problems were signicantly more likely to

show signs of premeditation than men with criminal legal problems.

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

28

SECTION 3: A Review of the Research on Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

Suicide is the leading cause of death in jails. The average annual suicide rate (2000 –2013) among jail inmates

(male and female) was 41/100,000. Men die by suicide in jails at a rate 1.5 times that of women. About half of

suicides in jails are among inmates over the age of 35. The suicide rates of adults in jails and prisons generally

increase with age (Figure 8). (Noonan, Rohloff, & Ginder, 2015)

Figure 8. Average Annual Suicide Rates, Inmates by Age

Average Annual Suicide Rates

per 100,000 Inmates by age, 2000-2013

55 or older

45-55

35-44

25-34

18-24

<17

Jails

Prisons

100 80 60 40 4020 200

Source: Data from Bureau of Justice Statistics, as cited in Noonan, Rohloff, and Ginder (2015).

.

Suicide attempts by both men and women (including those that occurred prior to incarceration) were reported

by 13 percent of inmates in state prisons, 6 percent of those in federal prisons, and 12.9 percent of those in

local jails (James & Glaze, 2006).

The latest U.S. Department of Justice data on mental health problems among inmates (James & Glaze, 2006)

reveal that as of 2005, “more than half of all prison and jail inmates had a mental health problem.” This includes:

ñ 56 percent of inmates in state prisons

ñ 45 percent of inmates in federal prisons

ñ 43 percent of inmates in jails

Seventy-four percent of state prisoners and 76 percent of female inmates in state prisons “who had a mental

health problem met criteria for substance dependence or abuse” (James & Glaze, 2006). Among state prison-

ers, 43 percent with mental health problems reported binge drinking. In contrast, 29 percent of state prisoners

without mental health problems reported binge drinking.

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

29

SECTION 3: A Review of the Research on Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (GBT) Men

Relatively little information is available about suicide rates among people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and

transgender (LGBT) because vital statistics data do not include information on sexual orientation or gender

identity. Gay and bisexual men have signicantly higher suicide attempt rates than their heterosexual peers

(Haas et al., 2011). However most of the research has been done on younger men. Some research indicates

that, at least among adolescents, gender nonconformity rather than sexual orientation per se is associated with

this elevated risk.

Several recent studies suggest that LGB people are also at increased risk for suicide (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2014;

Ploderl et al., 2013). There is evidence that older GBT men experience higher levels of depression and psycholog-

ical stress than heterosexual people (Services and Advocacy for Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Elders &

LGBT Movement Advancement project, 2010). An analysis that correlated mortality information from the National

Death Index with measures of prejudice from the General Social Survey found that LGB people living in commu-

nities characterized by a high level of prejudice against sexual minorities had an average life expectancy 12 years

shorter than their peers who lived in communities with a low level of prejudice. The average age at which LGB

people died by suicide in high-prejudice communities was 37.5 years compared to 55.7 years in low-prejudice

communities (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2014). The data were not broken out by sex or gender.

Data from the National Transgender Discrimination survey revealed elevated suicide attempt rates among trans-

gender people. Although these rates decline with age, the rate for transgender men in the middle years is higher

than that of the general population and of gay and bisexual men (Haas, Rodgers, & Herman, 2014).

Veterans

Historically, veterans have had lower suicide rates than their non-veteran peers (Kang & Bullman, 2009). How-

ever, this pattern is changing. An analysis of 2003–2008 NVDRS data (Kaplan, McFarland, Huguet, & Valen-

stein, 2012) found that male veterans had signicantly higher suicide rates than males who were not veterans

(although this pattern did not hold for men 65 years of age and older). An analysis of data from the U.S. Depart-

ment of Veterans Affairs (Hoffmire, Kemp, & Bossarte, 2015) found that “from 2000 to 2010, both the crude and

age-adjusted veteran suicide rates for men and women combined increased by approximately 25 percent while

the comparable nonveteran rates increased by approximately 12 percent.” The suicide rate for male veterans

was 20 percent higher than for men who were not veterans.

Hoffmire, Kemp, & Bossarte (2015) suggest that the rate of suicide among veterans may be related to (a) trau-

ma associated with combat, (b) interpersonal issues associated with deployment and re-entry into civilian life,

and (c) the demographics of the all-volunteer army.

Men 30–64 years of age have the highest suicide rate among patients who seek health care services from the

Veterans Health Administration (Blow et al., 2012). A majority of veterans who die by suicide are age 50 or

older (Kemp & Bossarte, 2012).

In a study of veterans who died by suicide, veterans ages 35–64 “were more likely to be White, married, and

to have died in a rural area than their younger counterparts” (Kaplan et al., 2012). This study also found that

younger veterans were more likely to have intimate partner problems while older veterans were more likely to

have health problems. Veterans 35–44 were more likely to have received a mental health diagnosis than those

under the age of 35 or older than 44. Firearms were more likely to have played a role in suicides by older

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

30

SECTION 3: A Review of the Research on Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

veterans. Younger veterans who died by suicide were more likely to have a history of prior suicide attempts than

older veterans.

Murder-Suicide

Although incidents in which a person kills others, and then dies by suicide, are rare, they receive a great deal

of media attention. Little information on murder-suicides is available. A review of the literature (Eliason, 2009)

revealed the following:

ñ The murder-suicide rate in the United States is approximately 0.2–0.3/100,000 a year and is relatively stable.

ñ Most murder-suicides involve “a man killing his wife, girlfriend, ex-wife, or ex-girlfriend.” Some involve a

parent killing his or her children.

ñ The mean age of the perpetrators of murder-suicide is 40–50 years. This is older than the mean age of

people who perpetrate homicide.

Cohen, Llorente, and Eisdorfer (1998) found that while younger men tend to kill their wives and themselves

after marital discord, older couples who die in murder-suicides often have medical problems.

Schiff et al. (2015) found that 41 percent of men between the ages of 35 and 64 who died by suicide and had

criminal and/or legal problems (but did not have a history of mental health or substance abuse problems) had

committed or attempted homicide prior to their death. The majority of the victims of these homicides and at-

tempted homicides were intimate partners, former intimate partners, or family members.

Eliason (2009) concluded:

There are certain clinical presentations that should alert mental health professionals to be suspicious of the

risk of possible murder-suicide: a middle-aged man who is recently separated or facing pending estrange-

ment from his intimate partner and who is depressed and has access to rearms; or an older male who is

the primary caregiver for a spouse who is ill or debilitated, where there is a recent onset of new illness in the

male, depression, and access to rearms.

Risk Factors for Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

Risk factors associated with suicide can be divided into these three categories: individual or personal risk

factors (e.g., mental disorders), relationship or interpersonal risk factors (e.g., intimate partner problems), and

environmental or external risk factors (e.g., lack of access to behavioral health care).

Many of the major risk factors associated with suicidal behaviors among MIMY (Figure 9) are also major risk

factors for women and for men in other age groups (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Ofce of

the Surgeon General, & National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, 2012). These include:

ñ Prior suicide attempts

ñ Mental disorders

ñ Substance abuse

ñ Chronic disease and disability

ñ Social isolation

ñ Access to lethal means

ñ Lack of access to behavioral health care

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

31

SECTION 3: A Review of the Research on Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

Figure 9. Risk Factors for Suicidal Behaviors among MIMY

Major Risk Factors Associated with Suicidal Behaviors among

MIMY

SUICIDE

Of men ages 40–65 who died by suicide in the United States (2005–2010):

43.1 percent experienced depressed mood (Hempstead & Phillips, 2015)

36.8 percent had alcohol dependence or another substance problem (Hempstead & Phillips, 2015)

69.6 percent were currently not being treated for a mental health problem (Hempstead & Phillips, 2015)

3 7. 1 percent had intimate partner problems, for example, divorce, argument, or violence (Hempstead &

Phillips, 2015)

36.2 percent had job or nancial problems (Hempstead & Phillips, 2015)

54 percent used rearms (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014)

SUICIDE ATTEMPTS

Of men ages 35–64 who attempted suicide in the past year in the United States (2008–2013):

40.6 percent had experienced a major depressive episode

41.7 percent had been binge drinking

32.4 percent had a substance abuse disorder

42.2 percent did not receive mental health treatment

30.4 percent were disabled and could not work

39.3 percent had an income of less than 100 percent of the Federal Poverty Line

40.6 percent had a criminal history (arrested and booked)

Source: Data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration (2013).

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

32

SECTION 3: A Review of the Research on Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

Mental Disorders

Draper, Kolves, De Leo, & Snowdon (2013) found that 75.1 percent of people who died by suicide had a

psychiatric disorder—although this percentage decreases with age. A meta-analysis of psychological autopsy

studies of people (all ages and both sexes) who died by suicide found that “87.3 percent . . . had been diagnosed

with a mental disorder prior to their death” (Arsenault-Lapierre, Kim, & Turkecki, 2004). Arsenault-Lapierre et al.

(2004) also reported that men who died by suicide tended to be diagnosed with substance abuse, personality

disorders, and/or childhood disorders.

An analysis of NVDRS data revealed that 43.1 percent of men 40–64 years of age who died by suicide had

experienced depressed mood. This percentage was not signicantly different from that of women who died by

suicide (Hempstead & Phillips, 2015).

NSDUH data (SAMHSA, 2013) revealed that 40.6 percent of men in the 35–64 age group who attempted

suicide in the past 12 months and 45.2 percent of those who had serious suicidal thoughts also experienced a

major depressive episode during that period. The percentages for women were 62.9 percent and 55.1 percent,

respectively. The percentage of younger adults of both sexes who had attempted or seriously thought about

suicide and suffered a major depressive episode was also extremely high.

There is evidence that clinicians systematically fail to identify depression in men because of “the widespread

use of generic diagnostic criteria that are not sensitive to depression in men” (Oliffe & Phillips, 2008). Hemp-

stead and Phillips (2015) found that 69.6 percent of men who died by suicide were not currently in treatment

for any mental health issues.

Alcohol and Drugs

NVDRS data reveal that 36.8 percent of men (age 40–64) who died by suicide were dependent on alcohol or

had another substance abuse problem. Men who died by suicide were signicantly more likely to be dependent

on alcohol than women who died by suicide (although no difference was found in other substance problems)

(Hempstead & Phillips, 2015). Acute alcohol intoxication at the time of death is more common among men than

women, men with low education status, men and women in the 35–44 age group, and American Indians and

Alaska Natives (Kaplan et al., 2013).

Research has revealed a signicant association between the density of bars and retail liquor stores in an area

and the suicide rate in that area. The authors of some of these studies have suggested that policies that reduce

the density of liquor stores in a geographic area (e.g., restricting the number of liquor licenses in a neighbor-

hood, town, or county) may reduce the rate of suicide in that area (Khaleel et al., 2016; Giesbrecht et al., 2015;

Johnson, Gruenwald, & Remer, 2009; Escobedo & Ortiz, 2002).

NSDUH data show that the patterns of alcohol and drug abuse among MIMY who have attempted or thought

seriously about suicide are more similar to those of younger men than to women in the middle years. Substantial

percentages of MIMY who reported suicide attempts also reported binge or heavy alcohol use or substance or

alcohol use disorders (Table 3).

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

33

SECTION 3: A Review of the Research on Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

Table 3. Percentage of Alcohol and Drug Abuse Indicators (Past 12 Months) among Those

Reporting Suicidal Behaviors (Past 12 Months), by Sex and Age, 2008–2013

Men Attempts

(18–34 years)

Men Attempts

(35–64 years)

Women

Attempts

(35–64 years)

Men Serious

Thoughts

(18–34 years)

Men Serious

Thoughts

(35–64 years)

Women Serious

Thoughts

(35–64 years)

Binge Alcohol

Use

50.7% 41.7% 28.7% 50.6% 34.6% 19.5%

Heavy Alcohol

Use

22.6% 18.7% 5.4% 21.7% 13.8% 5.3%

Substance

Use Disorder

51.3% 32.4% 24.7% 44.3% 24.6% 16.3%

Alcohol Use

Disorder

42.9% 26.3% 19.2% 34.2% 20.5% 12.3%

Illicit Drug

Disorder/

Prescription

Drug Use

Disorder

30.8% 16.5% 8.9% 23.2% 9.9% 6.2%

Alcohol and/

or Drug Use

Treatment

17.2% 21.2% 12.9% 9.5% 9.4% 6.5%

Source: Data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2008-2013, Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration (2013).

An analysis of NVDRS data revealed that, in every age group, blood alcohol content was higher in men than in

women who died in suicides associated with rearms, hanging, or poisoning (Conner et al., 2014). This indi-

cates that intoxication is a risk factor for suicide among people whose alcohol use does not rise to the level of a

diagnosable disorder. The association between intoxication and suicide is usually attributed to alcohol’s effects

on inhibition, judgment, and impulsivity. It has also been suggested that depressed men may self-medicate with

alcohol or drugs rather than seek mental health care. Alcohol and drug use can thus conceal depression as well

as amplify the suicide risk in men suffering from depression (Brownhill & Wilhelm, 2002).

Means of Suicide

In 2014, 52 percent of suicides among men 35–64 years of age involved rearms (compared to 32 percent

among women in this age group) (CDC, 2014). Firearms are more likely to result in a death than other meth-

ods of suicide. The fact that MIMY tend to choose rearms as a means of self-harm has a major impact on the

suicide rate of this age group.

The rate of rearms-related suicide among men in the 35–64 age group is higher than among men ages 18–34

and much higher than among women ages 35–64 (Table 4).

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

34

SECTION 3: A Review of the Research on Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

Table 4. Suicide Death Rates per 100,000 by Means, 2014

Means Males (ages 18–34) Males (ages 35–64) Females (ages 35–64)

Firearms 10.84 14.52 2.92

Hanging (Suffocation) 8.29 7.57 2.02

Poisoning 1.70 3.85 3.57

All Means 22.70 28.13 9.29

Source: Data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014).

A study of suicides in workplaces in the United States (2003–2010) found that 84 percent of suicides in pro-

tective service workplaces (e.g., rst responders and animal control workers) involved rearms, compared to

50 percent of suicides in farming, shing, and forestry, and 29 percent among building and grounds cleaning

occupations (Tiesman et al., 2014).

Suffocation as a means of self-harm has been rising. Between 1999 and 2010, the percentage of suicides by

suffocation increased by 75 percent for men (i.e., from 18 to 24 percent) and by 115 percent for women (i.e.,

from 12 percent to 18 percent) (CDC, 2013).

Chronic Medical Conditions and Disability

Medical conditions associated with suicide include arthritis, cancer, asthma, peptic ulcers, cardiovascular dis-

ease, epilepsy, HIV, Huntington’s disease, chronic migraines, and multiple sclerosis (Berman & Pompili, 2011;

Webb et al., 2012). Although the research on the relationship between physical illness and disability and suicide

risk among MIMY is limited, many of these conditions begin to emerge as men enter this age range. For exam-

ple, the rates of heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and arthritis all start increasing when men (and women) are in

their 40s and continue to increase through older adulthood (Blackwell, Lucas, & Clarke, 2014).

The association between chronic medical conditions and suicide is often attributed to the fact that these con-

ditions can be associated with chronic pain (HHS, 2012; Tang & Crane, 2006; Webb et al., 2012). Schiff et

al. (2015) found that physical health conditions were one of four risk factors associated with suicides by men

between the ages of 35 and 64 who were not identied as having mental health or substance abuse problems,

which provides some evidence that chronic medical conditions can contribute to suicide risk even in the ab-

sence of depression. This research also found that suicides associated with health problems were more likely to

be triggered by a recent crisis after a period of long-term risk than by a crisis alone.

Disability has also been associated with suicide risk. NSDUH data from 2008 to 2013 (SAMHSA, 2013)

revealed that 30.4 percent of men, and 44.3 percent of women, ages 35–64 who attempted suicide within the

12 months preceding the survey were disabled and could not work. In this age group, 25.4 percent of men and

24.2 percent of women who had serious thoughts of suicide were also disabled and could not work.

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

35

SECTION 3: A Review of the Research on Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

Economic Factors

There is evidence that economic factors play a role in overall suicide rates, and especially among MIMY. For

example, NSDUH reveals that 39.3 percent of MIMY who attempted suicide had an income below the Federal

Poverty Line (SAMHSA, 2013).

Efforts to understand the relationship between suicide and socioeconomic status have been hampered by

the lack of income and income proxies in large databases such as the National Vital Statistics System and the

National Violent Death Reporting System. Educational attainment and occupational skill level are often used

as proxies for income and wealth in suicide research. Phillips (2010) found that suicide rates decreased with

educational attainment (Table 5).

Table 5. Suicide Rates per 100,000 for Men by Educational Attainment, 2005

Education Age: 40–49 years 50–59 years

12 or fewer years 34.89 31.03

13–15 years 17.65 18.55

16 or more years 13.46 16.61

Sources: Data from National Vital Statistics System and U.S. Census Bureau, as cited in Phillips (2010), Table 2.

The authors suggested that people with less education may be more at risk for suicide because of general

nancial strain and because they cannot afford care for chronic diseases that are associated with suicide risk.

Although the relationship between educational attainment and suicide also held for women, it was not as pro-

nounced as for men.

NSDUH data showed that although the risk of suicide attempts for MIMY is greater for high school graduates

than those who do not complete high school, this risk decreases with subsequent levels of educational attain-

ment (Table 6).

Table 6. Educational Indicators among Men and Women Who Reported

Suicidal Behaviors in the Past 12 Months, 2008–2013

Education

Men Attempts

(35–64 years)

Women Attempts

(35–64 years)

Men Serious

Thoughts

(35–64 years)

Women Serious

Thoughts

(35–64 years)

Less than High

School

29.5% 18.5% 17.6% 12.2%

High School

Graduate

33.7% 29.5% 31.9% 29.1%

Some College 22.5% 33.8% 25.5% 31.9%

College Graduate 14.3% 18.2% 25.1% 26.8%

Source: Data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2008-2013, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2013).

Preventing Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

36

SECTION 3: A Review of the Research on Suicide among Men in the Middle Years

The 18–34 age group was not included in this NSDUH analysis because a signicant number of members of that

age group will eventually complete high school or college (even if they had not done so at the time of the survey).

A meta-analysis (Milner, Spittal, Pirkis, & LaMontagne, 2013) found that people in low-skill-level occupations

were at a higher risk for suicide than people in high-skill-level occupations and the general working age popu-